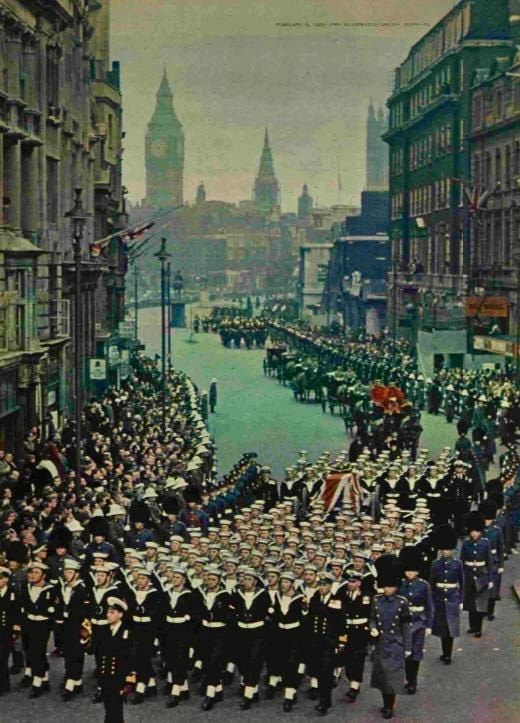

How the Queen orchestrated Churchill's funeral sixty years ago this week

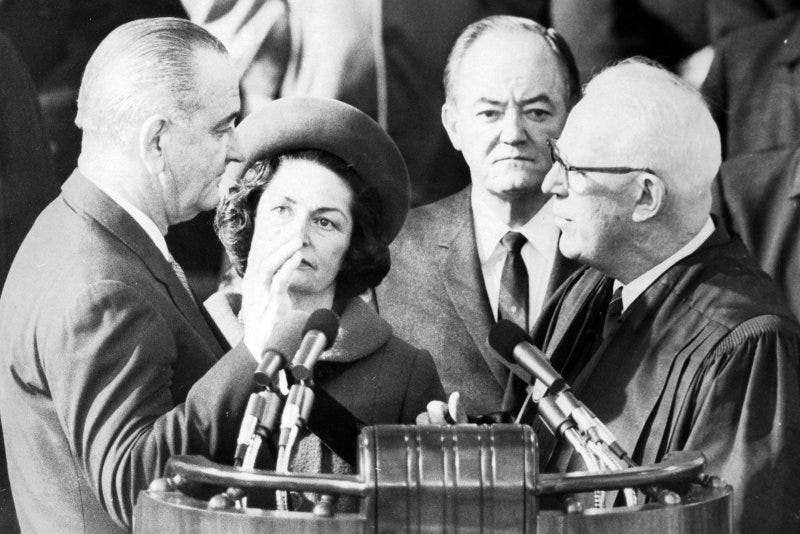

A frustrated President Johnson had to stay home because of illness, but former President Eisenhower attended as a guest of the Churchill family

On Saturday January 23rd, 1965, three days after President Lyndon Johnson was sworn into office on a frigid day in Washington, he was admitted to Bethesda Naval Hospital with a “rasping cough” that turned out to be severe respiratory illness. The next day, Sir Winston Churchill died at age ninety after multiple strokes. Those two events set in motion extraordinary maneuvers on both sides of the Atlantic as Britain honored the former prime minister who was a partner of Franklin D. Roosevelt during the Second World War.

Queen Elizabeth first authorized a confidential funeral plan for Churchill—then in his second term as prime minister—in 1953 after he suffered a stroke. Code-named “Operation Hope Not,” the plan took on extra urgency in 1958 when Churchill nearly died from pneumonia. The Queen decided that he should be given a full state funeral—a rarity for a “commoner”—on the grand scale of the funeral of the Duke of Wellington in 1852. “It was entirely owing to her that it was a state funeral,” Churchill’s daughter Mary Soames told me. “She indicated that to him several years before he died, and he was gratified.”

“A generous providence gave us Winston Churchill”

From his hospital room in Maryland on January 24th, Johnson praised the wartime commander who led Britain and its allies to victory over Nazi Germany and Japan in the Second World War. “When there was darkness in the world, and hope was low in the hearts of men, a generous Providence gave us Winston Churchill. As long as men tell of that time of terrible danger and of the men who won the victory, the name of Churchill will live. He is History’s child, and what he said and what he did will never die.”

The following days leading to the funeral on January 30th unfolded with a series of top-secret memoranda and transatlantic telephone calls as Johnson pressed his senior advisers and doctors to make it possible for him to attend the historic event that would be seen on television by 350 million people around the world. David Bruce, the United States Ambassador to the Court of St. James’s, was the man in the middle, and he recorded the confidential deliberations in his diary, revealed here in detail, along with fresh commentary on the funeral itself.

“His will is obstinate”

By Monday January 25th, Johnson was running a fever and suffering from “an acute bronchial condition,” wrote Bruce. Nevertheless, the President “has made evident his hope of attending the funeral despite medical opposition.” Although Johnson had already suffered a half-dozen bouts of pneumonia, “his will is obstinate, like Churchill’s. His intimates disapprovingly predict he will make the journey.”

At a dinner that night hosted by British diplomat Harold Caccia, Bruce found himself “locked in a telephonic grip” with Lloyd Hand, Johnson’s newly appointed Chief of Protocol. “He said our talk was to be completely secret. I was to mention it to nobody in the Embassy or the British Government.”

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to ROYALS EXTRA BY SALLY BEDELL SMITH to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.