The Royal Family's First American Thanksgiving

In November 1942 King George VI led his nation in thanking American troops for joining the battle against the forces of facism during the Second World War

This Royals Extra is appearing several days early to mark the Thanksgiving holiday. The next edition will be during the first weekend of December. I’m also offering this feature in its entirety, with no paywall, to all subscribers in the spirit of the day. Happy Thanksgiving to everyone!

After Japan’s surprise bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, Britain and America declared war on Japan. When Hitler followed on the 11th by declaring war on the United States, Britain finally had the full-fledged American support it desperately needed after two years of fighting the Nazis and their Axis allies with the assistance of armed forces from Canada, Australia, New Zealand and elsewhere across the British Empire. Until then, President Franklin D. Roosevelt had been helping in every way “short of war” with munitions, ships, and other essential supplies. He had strong relationships with both King George VI and Winston Churchill, who planned vital war strategy with him. The King and FDR had been secretly corresponding since April 1940. “We are proud indeed to be fighting at your side against the common enemy,” George VI wrote to Roosevelt on December 10, 1941.

The first 4,000 American troops landed in the United Kingdom on January 26, 1942, and by the end of the year that number had swelled to 300,000. On November 7th, a combined force of more than 100,000 British and Americans landed in North Africa for the first major joint operation of the war. When the Allies took control of Morocco and Algeria, the British government ordered church bells to peal throughout the country.

There was much fighting still to be done, and after serious setbacks for the British earlier in the year, the Americans helped shift the momentum toward victory. As an expression of their gratitude, the British people paid special tribute to the American service men and women with Thanksgiving Day celebrations, many in bomb-battered buildings. Chief among the celebrants were King George VI and Queen Elizabeth, who invited more than two hundred American guests to Buckingham Palace, which by then had been bombed eight times and had numerous boarded windows. Although it was a private event and not recorded by photographers, the remarkable gathering described below was pieced together from the diaries of George VI and a friend of his daughters, a memorandum by a prominent admiral, and other contemporary accounts.

“Hedge of khaki”

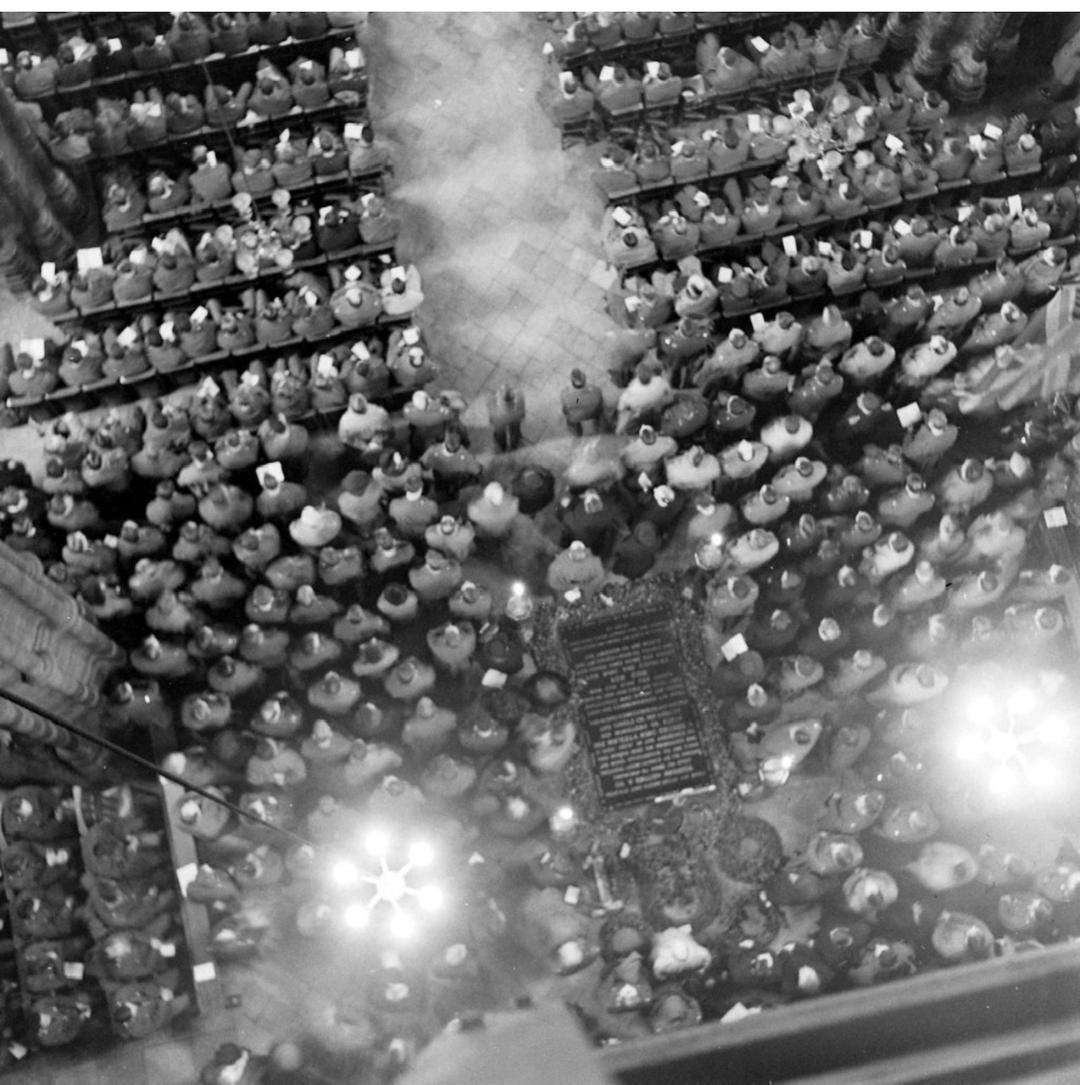

In an unprecedented non-denominational service, Britons honored 3,500 soldiers, sailors, airmen, and members of the American women’s services who assembled in Westminster Abbey, the ancient heart of the monarchy and the Church of England that had been severely bombed in May 1941. They stood in the aisles and crowded around the tomb of Britain’s Unknown Warrior, resembling a “hedge of khaki.” “The air raid damage suffered by the Abbey has been all but concealed,” noted The Times, “but sandbags surmount the high altar,” where the Dean of Westminster draped the Stars and Stripes.

Four uniformed chaplains conducted the service. U.S. Ambassador to Britain John G. Winant read a Thanksgiving Proclamation from President Roosevelt that began, “It is a good thing to give thanks unto the Lord. Across the uncertain ways of space and time our hearts echo those words.” A choir of thirteen soldiers sang the anthem, “We Adore Thee, O Christ,” and the congregation sang “America the Beautiful,” “Lead on O King Eternal,” “The Star-Spangled Banner,” and “God Bless America.”

At Buckingham Palace, the King and Queen, along with sixteen-year-old Princess Elizabeth and twelve-year-old Princess Margaret, gave an “Afternoon Party” for two hundred officers from the United States Army, Air Corps, and Navy, as well as twenty-five American nurses. Also present were Ambassador Winant and top brass from the British military including the King’s cousin, Vice-Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten, Admiral of the Fleet, and his wife Edwina. Prime Minister Winston Churchill brought his twenty-year-old daughter Mary, who was serving in the Auxiliary Territorial Service. “It is to commemorate the First Harvest Festival of the Pilgrim Fathers in New England in 1621,” George VI wrote in his diary.

In this holiday season, why not give a Royals Extra subscription to someone who shares your interest in the British royal family and its history?

“Bright and pleasant to talk to, just like her mother”

The royal family met a few of the senior American officers in the Bow Room on the ground floor, which Admiral Harold Stark, the commander of the U.S. Naval Forces in Europe, described as “one of the large warm rooms.” They chatted briefly with the King and Queen and the “two dear little girls, and incidentally, Elizabeth is not so little anymore. She is a very nice-looking girl, bright and pleasant to talk to, just like her mother. The younger one, Margaret Rose, is tiny for her twelve years, but also bright as she can be.”

The Prime Minister and other British dignitaries—among them First Sea Lord Sir Dudley Pound, Chief of the Imperial General Staff General Sir Alan Brooke, and Chief of the Air Staff Air Chief Marshal Sir Charles Portal—greeted the King and Queen before they all joined the large group of guests in the Grand Hall. The two girls were accompanied by their neighbor near Windsor Castle, nineteen-year-old Alathea Fitzalan Howard, who wrote in her diary that Princess Elizabeth “wore that awful blue silk frock with the little pleated cape, which is the worst thing she could possibly wear with her figure,” and Princess Margaret “had a nondescript silk frock on.”

A buffet table stretched the length of the hall offering “a bountiful repast of whatever one wanted to eat or drink,” noted Admiral Stark. All the guests shook hands with the King and Queen in a receiving line as a string band of the Grenadier Guards played chamber music in the corner. The four members of the royal family took their time mingling as everyone ate and drank. “It was very informal, everybody felt at home, and had a fine time,” wrote Stark.

“They have very good manners”

The party ran from 3:15 to 5:30. “We stood for nearly 3 hours,” the King wrote in his diary. “They have very good manners & waited for their turn. I spoke to 3 or 4 of them at the same time. They all seem happy here.” Alathea later said that Princess Elizabeth was “good at trying to find words for strangers, but it is a great strain for her.” Margaret, on the other hand, “burbles away naturally and easily.”

Elsewhere around Britain, scores of services and celebrations took place in more than fifty towns. In central London “there was an air of happy thankfulness,” noted The Times, as hotels, restaurants, cinemas, and shops flew the American flag. American troops gave Thanksgiving Day parties for British children, including two hundred orphaned by the war who were hosted by the Eighth Air Force. The British were mindful of the origin of Thanksgiving with pilgrims who sought religious freedom from the Church of England by fleeing to the New World.

“My compatriots”

At Plymouth, Virginia-born Lady Astor— the first woman to take a seat as a Member of Parliament after being elected in 1919—presided over a ceremony at the Mayflower Stone, where the Pilgrim Fathers set sail for America. Australian airmen, Canadian firemen, and British sailors joined the Americans for the commemoration. Lady Astor called the American soldiers “my compatriots” and said it pleased her “to see the fighting men of my two countries standing side by side.”

In addition to the service at the Abbey, two other bomb-damaged houses of worship in London observed Thanksgiving with prayers and readings. Bishop James Dey, the Vicar Delegate for the American forces in Great Britain, sang a solemn high mass at Westminster Cathedral in London. Like the Abbey, the cathedral had been hit hard by German bombing raids. But the service at the New West End Synagogue in Bayswater had particular resonance.

“The inestimable privilege of fighting on their feet”

The synagogue had been targeted by bombs on Yom Kippur during the Blitz in October 1940. Two years later, Members of Parliament were gathering evidence of “barbarous and inhuman treatment” of Jews by the Nazis. On Thanksgiving Day in 1942, The Times reported that while presiding over the service, Chaplain Judah Nadich, the senior Jewish chaplain for the U.S. Army in Europe, publicly deplored the Nazi atrocities. “The hearts of Jews bled for their suffering kinsfolk undergoing Sisyphean tortures in the hellholes and concentration camps of Nazi-occupied lands,” he said. “It was not by accident that the Nazis paid them the high honor of singling the Jews out as their first enemies. Nazism and Judaism stood at diametrically opposite poles. To those Jews who had the privilege of wearing the uniform of a free people had been given the inestimable privilege of fighting on their feet, instead of dying on their knees.”

Exactly three weeks later, on Thursday December 17, Anthony Eden, Britain’s Foreign Secretary, rose in the House of Commons to read an official declaration from Britain and eleven other Allied nations condemning the German authorities for “carrying into effect Hitler’s oft-repeated intention to exterminate the Jewish people in Europe.” Knowledge of the “bestial policy of cold-blooded extermination…can only strengthen the resolve of all freedom-loving peoples to overthrow the barbarous Hitlerite tyranny” and to “reaffirm their solemn resolution to ensure that those responsible for these crimes shall not escape retribution.” As Eden spoke, “a hush fell,” and on his conclusion, all the members of Parliament stood for two minutes of silence. Yet other than vowing to give asylum to victims of Nazi barbarity, retribution would not come for nearly three years, after victory and the liberation of Europe.

Thank you Sally, what a great story. I imagine the Brits were also thanking God for getting us into the war officially.

thank you sally... happy thanksgiving...